Charlie Adams probably could have been the executive director of the National Federation of State High School Associations if he wanted to be. But he didn’t want to be. He wanted to work for the boys and girls and North Carolina.

Charlie Adams probably could have been the executive director of the National Federation of State High School Associations if he wanted to be. But he didn’t want to be. He wanted to work for the boys and girls and North Carolina.

When colleagues approached him about seeking the national executive director’s post in 1993, he quickly turned them down. Instead he invited his friend Bob Kanaby, the head of the New Jersey State Interscholastic Athletic Association (NJSIAA), to an NCHSAA-sponsored chemical awareness conference at Wrightsville Beach.

There, on lengthy walks along the shore, Adams convinced Kanaby to accept the national position if it was offered.

“I didn’t want to leave my home state. I wanted to help the boys and girls here ,” Adams said.

Adams, 81, died peaceably at his home in Chapel Hill on September 17. He was holding is wife Sue’s hand.

He figuratively had held the hands of 100s of thousands of North Carolina high school athletes for years.

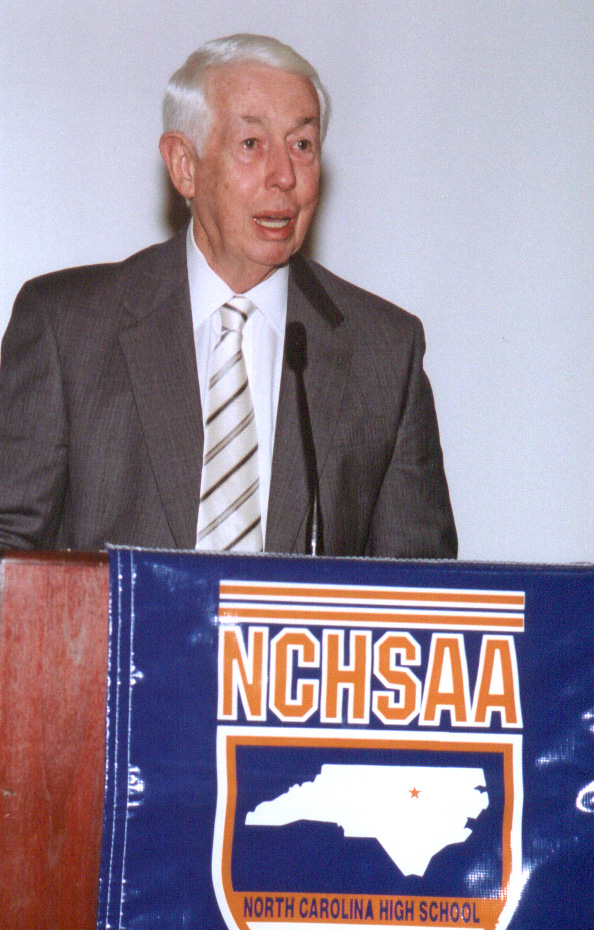

He was the executive director of the N.C. High School Athletic Association for 26 years that were filled with innovation and excellence.

When Adams joined the NCHSAA as an assistant in 1968, the NCHSAA was led by executive director Simon Terrell and similar to most other state high school athletic associations throughout the nation. The NCHSAA had a small office in a basement room at the University of North Carolina.

The NCHSAA conducted state championships in a handful of sports for boys, none for girls, and it helped organize schools into conferences. It also enforced rules and regulations, sometimes keeping teams from participating in the playoffs.

But Adams knew the association could be so much more. “Everybody was looking at us as a regulatory organization,” he said. “We were a service organization, or at least we were going to become one.”

Adams first job at the NCHSAA was to consolidate the four organizations that regulated high school athletics in North Carolina into the NCHSAA. The Robeson Indian High School Athletic Association joined in 1968, Adams’ first year as an assistant.

The schools in the N.C. High School Athletic Conference, the organization for black high schools in the segregated state, joined the NCHSAA in 1969 and the Western N.C. Activities Association schools joined in 1977 .

Willie Bradshaw, who was coaching at the all-black Durham Hillside at the time, said he knew of no other person who could have brought about the consolidation so smoothly.

“Charlie was honest and he had integrity,” Bradshaw, who is now deceased, said years later. “There were a lot of people who thought separate, but equal would work, but Charlie and a lot of other people knew we had to come together. Some people fought us every step of the way, but Charlie never faltered.”

“Charlie was honest and he had integrity,” Bradshaw, who is now deceased, said years later. “There were a lot of people who thought separate, but equal would work, but Charlie and a lot of other people knew we had to come together. Some people fought us every step of the way, but Charlie never faltered.”

Terrell, who was Adams’ basketball coach at Cary High in 1954 when the Imps won the state 1A title, retired as executive director in 1984. Adams succeeded him and the changes began immediately.

Creating an atmosphere of service was at the top of Adams’ list.

“We’ve got rules and we have to enforce them. We are the mean old guys in Chapel Hill occasionally,” Adams said. “But every day, we can be doing something good for the boys and girls of North Carolina.”

Boys and girls of North Carolina. Charlie Adams said that a lot. But in time, the phrase meant the boys and girls of the United States.

Innovation

During his 26 years as the executive director, the NCHSAA became the national leader by establishing an endowment fund to insure there would be funds for state championship competition; by moving state championships to major venues; by creating a student services program that stressed academics, citizenship and character development; by classifying the championships in all sports; and by creating state championships for girls’ sports.

He pushed to have a state record book and a hall of fame. He wanted to highlight the past, but not be hindered by it.

The NCHSAA offices were moved from the basement to the penthouse, a standalone building on Finley Golf Course in Chapel Hill. The office is filled with NCHSAA staff that oversee the myriad of programs that the NCHSAA instigated during Adams’ tenure.

Adams was a visionary and when he looked to the future, the vision wasn’t always positive.

He saw the growing influence of club teams and understood the ramifications long before most people. He realized that many club programs were unregulated and were devoted solely to sport, unlike educationally-based high school athletics.

Club teams can travel extensively, have few if any eligibility rules, can provide players with food and gifts, can hire and fire coaches, and can assemble teams that college recruiters want to see play.

“They can do things that high school teams can’t do, and really shouldn’t be doing,” Adams said. “High school programs need to do what they do best. We are a co-curricular part of the school. We teach life lessons through athletics. That is service and that is what we are going to emphasize. “

Adams insisted that high athletics had to be based on character development. He believed American society valued sportsmanship, integrity, self-sacrifice, teamwork, respect, knowing how to handle defeat and knowing how to handle success. Athletics taught how to strive toward goals while keeping the quest in the proper perspective.

“Those are the things that we do best,” he said. “And those are the things that we have to do better in the future.”

And high school sports had to be fun.

And high school sports had to be fun.

“That’s the No. 1 reason kids play,” Adams said. “They want to have fun. I know I sure did.”

He had so much fun, that almost 70 years later, Adams was still meeting regularly with his old teammates and the players that he coached.

He met regularly with other high school athletic executive directors who wanted the details of the NCHSAA’s innovations. No other state had been able to build an endowment. How could the NCHSAA afford to give most of playoff revenue to the teams and still play on neutral sites? And, perhaps asked most often, how did the NCHSAA manage to have such great relationships with coaches, athletics directors, legislators, superintendents and school boards?

Of all the things that Adams did, building relationships was probably what he did best.

Of all the things that Adams did, building relationships was probably what he did best.

And he wasn’t scared to fail. He was willing to try something different and there is a risk in that. He often pointed to a failed experiment, adding a secondary state playoff in football for teams that didn’t qualify for the state championship playoffs, as the impetus for one of the NCHSAA’s greatest successes . . . expanded playoffs.

The experiment was sparked by outstanding teams, occasionally a 9-0-1 team, not qualifying for the playoffs. The idea to reward those teams, but the experiment quickly became known as “the losers’ tournament” and was generally disliked by the member schools.

But on the heels of that experiment came an expansion of the playoffs with more team advancing. Several teams who would not have advanced under the previous system have won state titles.

Some failures bothered Adams, though. He was disappointed when he saw poor sportsmanship. At an NCHSAA basketball championship at the Smith Center, some players’ exuberance resulted in apparently taunting the opposing teams fans.

“For the first time in my life, I am embarrassed to be associated with high school sports,” he said.

He later said that sportsmanship was something you had to work on every day. You wish you could develop a day, a week, a month, a year to improving sportsmanship, put the result in a bottle and have the job done.

“But it is not that way,” he said. “If you are going to teach values, you have to teach them every day.”

Conducting state playoffs. Enforcing rules. That was the easy stuff. The hard thing was doing what was best for the boys and girls day after day. That was Adams’ goal.

As far as I know, Adams never regretted the long beach walks with Kanaby, when two men who could pick up the mantle of leading the nation’s high school athletic associations discussed the future.

Adams got a chance to be the national leader in 1997-98 when he was president of the National Federation and Kanaby was executive director. Adams visited in every state during his tenure and focused on bringing awareness of the growing influence of outside organizations on high school athletics.

Adams got a chance to be the national leader in 1997-98 when he was president of the National Federation and Kanaby was executive director. Adams visited in every state during his tenure and focused on bringing awareness of the growing influence of outside organizations on high school athletics.

He called it one of the best experiences of his life, but it also showed him that innovating is difficult on the national level, especially in a loose federation filled with very diverse members. A state association on the brink of bankruptcy, as some were during Adams’ tenure as president, aren’t interested in expanding programs.

“I learned that you can lead from where you are,” Adams once told me. “My place was here.”

From his first day until his last day as a high school athletics administrator, Adams never faltered in what was his lifetime goal . . . high school athletics had to be fun and the boys and girls had to get more from participating than just having fun.

Adams is a member of the N.C. Sports Hall of Fame, the NCHSAA Hall of Fame, the National High School Hall of Fame, the N.C. Athletic Director Hall of Fame, the East Carolina Hall of Fame and the Cary Hall of Fame.

– Tim Stevens has known Charlie Adams since 1967 when Adams was dean of boys at Garner High. Stevens became Adams’ office assistant that year when a knee injury prevented Stevens from participating physical education classes. Stevens was a sports reporter for The News & Observer for 48 years.